1) What is it?

The Westlands Water District settlement agreement with the Department of Interior’s Bureau of Reclamation solves an obligation by Reclamation to provide drainage services to farmland on the San Joaquin Valley’s Westside. With the planned expansion of the Central Valley Project in 1962 it was understood that along with irrigation water, a drainage system would be needed to carry away salts and minerals that would ultimately be harmful to farmland. Drainage is not a new problem to this area. In fact, over 4,300 years ago Mesopotamian farmers suffered the same fate by irrigating land without an effective way to drain away excess water and salts. Cuneiform tablets from the era provide a record of crop damage that Mesopotamians knew were the result of salt build-up.

When science took a back seat to politics in the 1980s, the planned 207-mile San Luis Drain was prematurely terminated at Kesterson Reservoir. It was believed by State and federal biologists that water supplying Kesterson would be a benefit to local wildlife. Sadly, the same evaporation of water that doomed Mesopotamian farmers also occurred at Kesterson, leaving behind salts and minerals that poisoned wildlife. The 82-mile completed portion of the drain was closed, leaving Reclamation with no solution to its contractual obligation to provide a drainage system for that part of the Central Valley Project. For the last 30 years courts have agreed that Reclamation is obligated to provide a drainage solution. Current estimates put that cost at $3.5 billion.

2) Why is this good for the public?

Numerous court decisions are clear stating that Reclamation must provide a drainage solution to the Westside. It is a scientific fact that was well known when the water supply project was built. But solving the drainage dilemma may not involve constructing an actual canal or pipeline to carry drain water away from the region, which was the original plan. Several options have been proposed and evaluated based on their costs, effectiveness and community impacts. According to the Department of Justice, which approved the settlement agreement, meeting Reclamation’s contractual obligation would cost American taxpayers $3.5 billion. With Reclamation’s entire annual federal budget in the neighborhood of $1 billion, http://www.usbr.gov/facts.html, it’s simply not feasible to expect a $3.5 billion solution.

Under the existing settlement terms Reclamation has agreed to forgive a $350 million debt owed by Westlands for its share of Central Valley Project infrastructure. That alone is a 10-1 payoff in favor of taxpayers when compared to the potential drainage solution cost. Reclamation will also transfer ownership of a limited number of pumping plants, canals and pipelines originally built to serve the area covered by the settlement, a customary practice.

3) How much farmland is being retired and why?

Without a proper system in place to accommodate known drainage issues, other options must be considered. Individuals

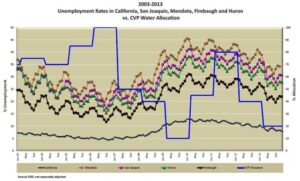

and organizations with no connection to farming have suggested retiring 200,000 acres or more of currently food-producing farmland. That alone could cost $2.8 to $3.6 billion, based on the current market value of farmland if Reclamation chose to buy out the landowners. The downside of that option is the harm to local economies and jobs that depend on farming. There is a direct correlation between land fallowing and unemployment.

As fallowing increases, so too are the costs that are shifted to local communities through unemployment, reduced access to health care, increased dependence on social welfare programs and diminished school enrollment.

Local food banks have seen dramatic increases in the number of families they serve in the last three to four years as a result of water supply cuts and drought.

“One out of three children in the Central Valley goes hungry every day, and the state’s drought conditions have only worsened the problem,” said Andrew Souza, president and CEO of Fresno-based Community Food Bank. “It is no longer just the poor and the homeless who are hungry; working families are also struggling to make ends meet.” http://prn.to/1hGm8wG

4) How is the drainage problem being solved?

Without construction of a physical drain or the permanent retirement of large swaths of farmland, other solutions must be used to effectively meet Reclamation’s drainage obligations. Westlands has agreed to fallow a minimum of 100,000 acres of farmland, or about 20 percent of the District to reduce the amount of drainage-impaired farmland in the area.

Adjacent to Westlands Water District is the San Joaquin River Salinity Management Program, operated by the Panoche Drainage District and Firebaugh Canal Water District. This project, identified as a “success story” by the EPA, reuses drain water from almost 100,000 acres of productive farmland to irrigate salt tolerant crops. By recycling saline drain water through various crops, including Jose tall wheat grass, alfalfa and pistachios, the project has been able to reduce the amount of selenium, salt and boron by up to 95 percent in water flowing out of the district. This recycled drainage water has been producing marketable crops for over 10 years.

With advanced water treatment, including already successful solar desalination, 100 percent of unwanted salts and minerals will be removed from the system. The cost to implement this technology could be hundreds of millions of dollars and will be the responsibility of Westlands. If the results are unsatisfactory, Reclamation will have the option to end water deliveries to the District.

5) How much water will Westlands get in the future?

Under the proposed agreement, Reclamation will reduce its contracted delivery of CVP water to Westlands by 25 percent to a total allotment of 895,000 acre-feet. The priority for water deliveries remains the same as before. In a year when water supplies are short and Reclamation delivers less than 100 percent, Westlands will share in the shortage the same as it has since CVP water deliveries began to fluctuate as far back as 1977.

This solution returns a level of certainty back to farms on the San Joaquin Valley Westside, while Reclamation and other federal agencies retain the right to manage the CVP with all of the current environmental protections under the Endangered Species Act.

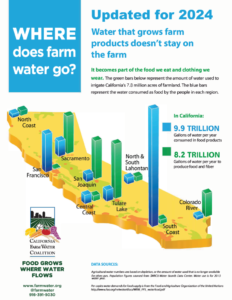

6) Do Westside farms matter to me?

All farming regions in California are important. That’s what gives us the diversity and quality of food products in the market. Each part of California plays an important role in our food supply because of the different climates and growing seasons. While we grow tomatoes in many parts of the state, they aren’t all grown at the same time, which wouldn’t be good for the market. Instead, food production follows the climate as it changes across the state throughout the year. When farmers harvest crops on the Westside they’re filling a place in the market that isn’t being filled with crops from somewhere else, either in California or across the country. That keeps fresh food available at the store when we want it and at a price that’s still affordable.

Westlands Water District produces $1 billion in food and fiber products each year with a corresponding $3.5 billion impact on the local economy. Rural communities depend on farms as a source of jobs and also as customers for local services, such as fertilizer sales, equipment sales and repair, fuel services and others. When farm water supplies are short the ripple effect can be felt throughout the region as businesses suffer and unemployment rises.