A Better Solution for Drought Resilience

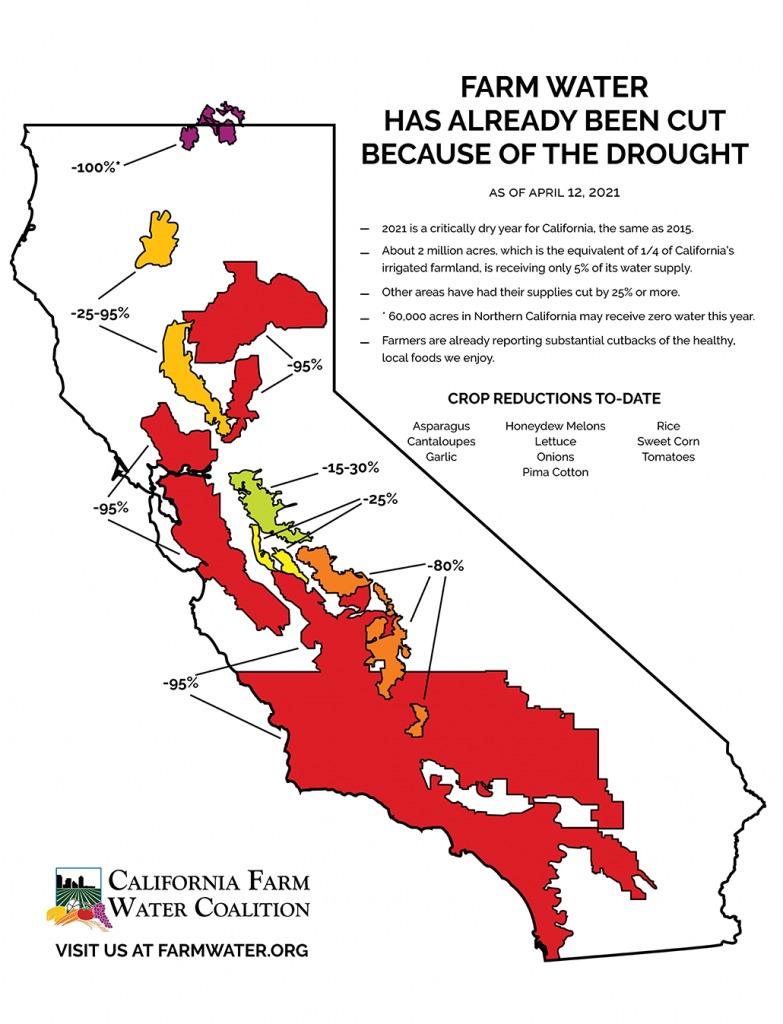

Map Shows 2021 Farm Water Supply Cuts

Click here to see the latest map. Updated: June 2021 California farms are bearing the brunt of this year’s short water supply and have been forced to reduce the acreage of popular California crops, such as asparagus, melons, lettuce, rice, tomatoes, sweet corn, and others. Water supply reductions mean fewer fresh fruits and vegetables for […]

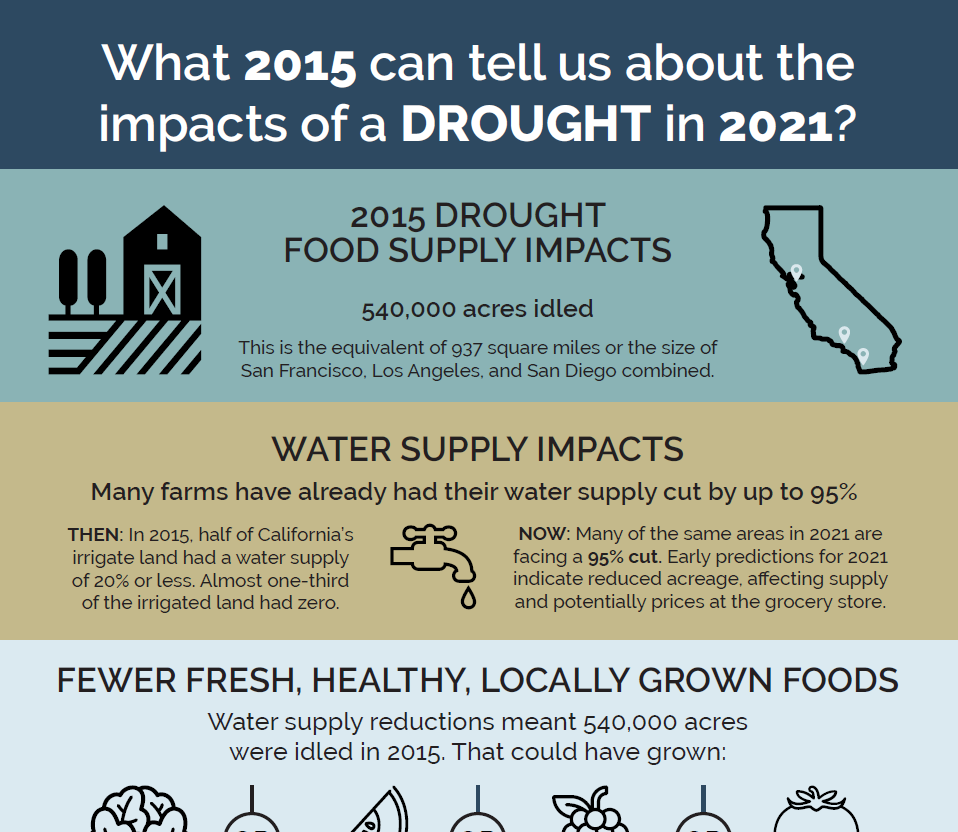

What can the 2015 drought tell us about the impacts of a drought in 2021?

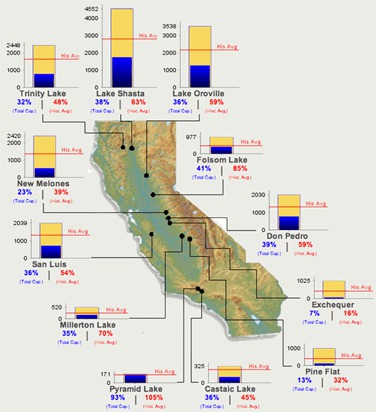

CDEC Reservoir Levels Map Copy

CDEC Reservoir Levels Map

California relies on water stored during wet years for use during dry years. Water storage, both above and below ground is critical to California. The map below shows how much water is in California’s major above-ground storage. These California’s Daily Reservoir Levels, per Department of Water Resources’ CDEC, is the water currently stored in […]

Guest Blog: Environmental Demands for Water Keep Expanding

By Justin Fredrickson, Environmental Policy Analyst, California Farm Bureau Federation Asked on the Public Policy Institute of California water blog “how much water nature needs,” the response of Mike Sweeney, the executive director of the Nature Conservancy’s California Chapter, was an attention-getter. At least it got mine. “Research,” Sweeney said, “shows that taking more than 20 […]

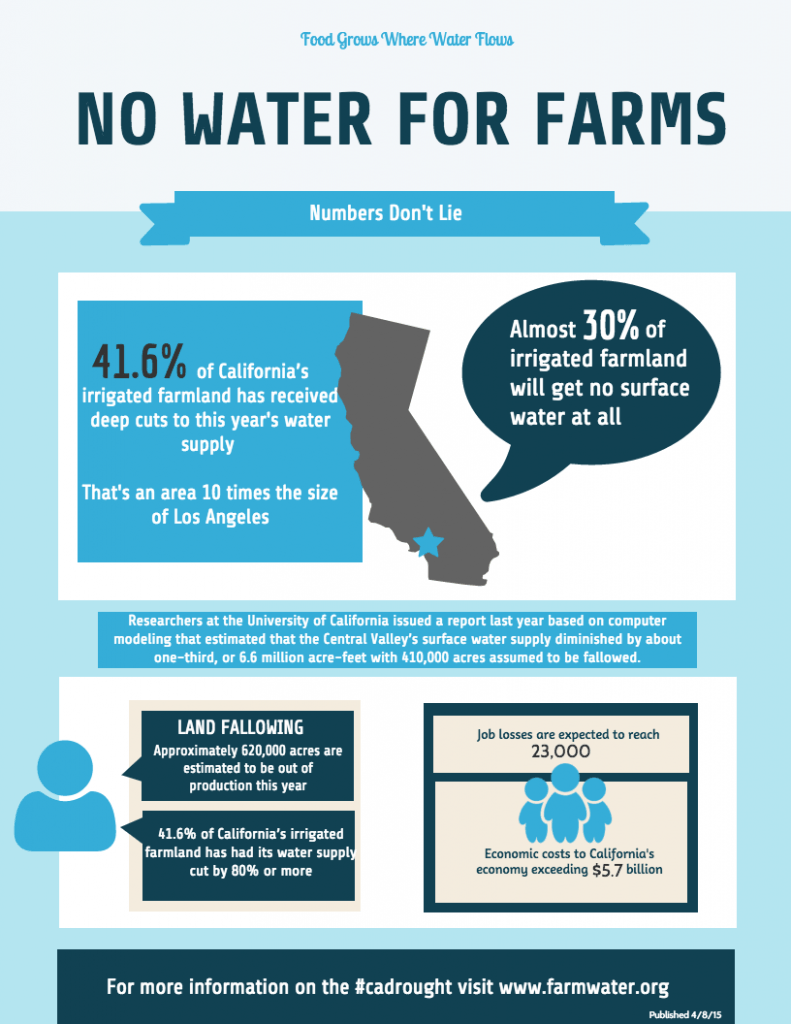

Over 41 percent of California’s irrigated farmland loses nearly entire surface water supply

Over 41 percent of California’s irrigated farmland will lose 80 percent or more of its normal surface water allocation this year, according to a new survey by the California Farm Water Coalition. The survey of agricultural water suppliers conducted the first week of April shows that 3.1 million acres, or 41.6 percent of California’s irrigated […]

SWRCB staff rejects urgent request for water

SWRCB staff rejects urgent request for water Despite concurrence among five State and federal agencies, a single State employee reversed a plan that would have delivered desperately needed water to most of drought-parched California. The decision is currently costing California water users about 2,000 acre-feet of water per day. A decision yesterday afternoon by State […]