One failure is we’re not capturing and storing nearly as much floodwater as we should.

Continue readingAre Curtailments a Balanced Water Use?

A Better Solution for Drought Resilience

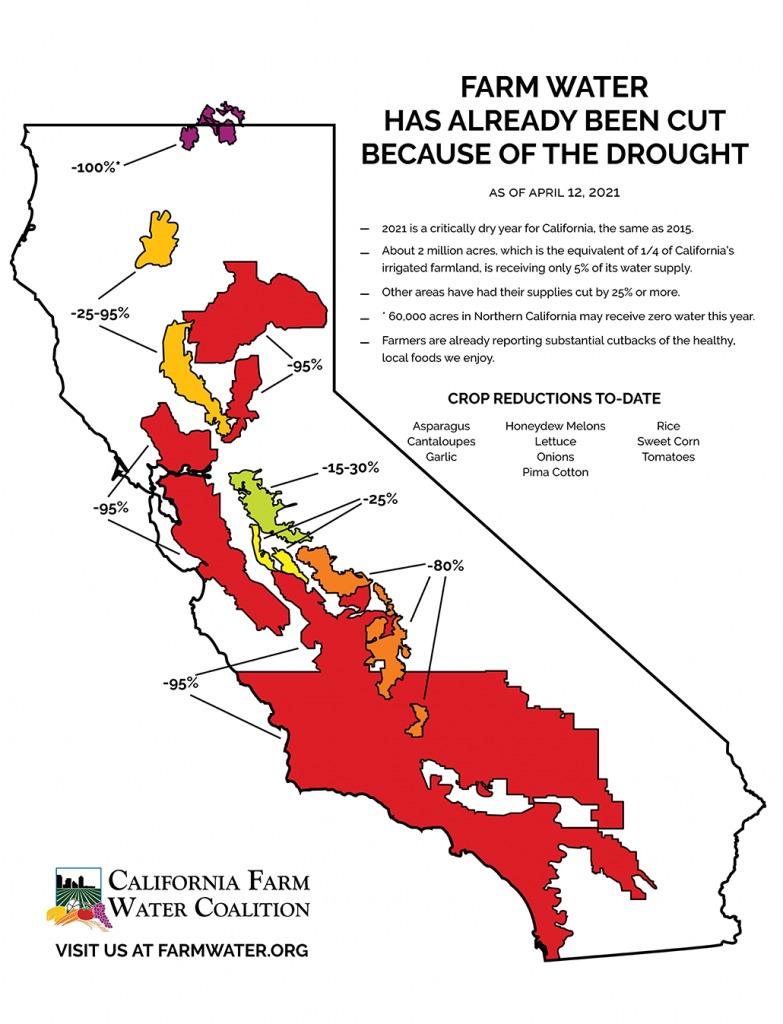

Map Shows 2021 Farm Water Supply Cuts

Click here to see the latest map. Updated: June 2021 California farms are bearing the brunt of this year’s short water supply and have been forced to reduce the acreage of popular California crops, such as asparagus, melons, lettuce, rice, tomatoes, sweet corn, and others. Water supply reductions mean fewer fresh fruits and vegetables for […]

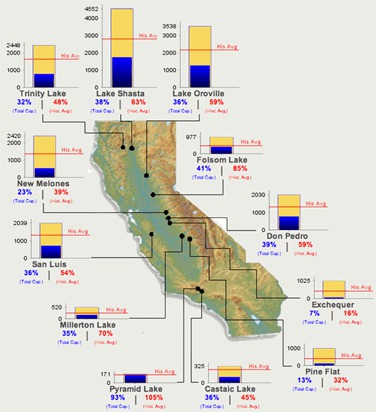

CDEC Reservoir Levels Map Copy

CDEC Reservoir Levels Map

California relies on water stored during wet years for use during dry years. Water storage, both above and below ground is critical to California. The map below shows how much water is in California’s major above-ground storage. These California’s Daily Reservoir Levels, per Department of Water Resources’ CDEC, is the water currently stored in […]

What do fish eat? Fish.

UPDATED 5-29-15 Assembly Member Rudy Salas (D-Bakersfield) has introduced AB 1201, a legislative bill that would require the California Department of Fish and Wildlife to develop and initiate a science-based approach that helps address predation by non-native species on Delta species. According to analysis prepared by Assembly Water, Parks and Wildlife Committee staff, the bill would accomplish […]

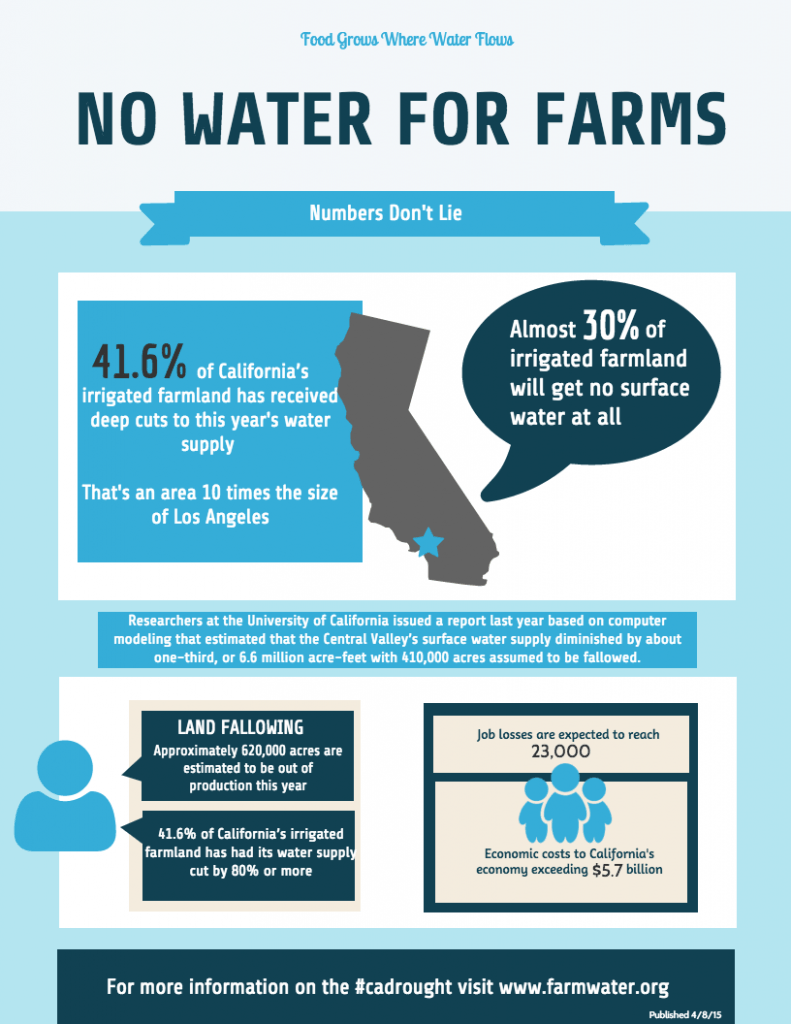

Over 41 percent of California’s irrigated farmland loses nearly entire surface water supply

Over 41 percent of California’s irrigated farmland will lose 80 percent or more of its normal surface water allocation this year, according to a new survey by the California Farm Water Coalition. The survey of agricultural water suppliers conducted the first week of April shows that 3.1 million acres, or 41.6 percent of California’s irrigated […]

Reservoir Levels Map

On the Abandonment of Federal Drought Legislation

On the Abandonment of Federal Drought Legislation “California’s Central Valley has shouldered more than its share of the pain brought on by reduced water deliveries and the drought. For more than 20 years, misguided environmental policies have drained California of over 20 million acre-feet of water – water that was originally intended to grow food. […]