One failure is we’re not capturing and storing nearly as much floodwater as we should.

Continue readingAbandoning Established Water Law Does Nothing to Produce or Save One Drop of Water and Puts Our Food Supply at Risk

Abandoning Established Water Law Does Nothing to Produce or Save One Drop of Water and Puts Our Food Supply at Risk

Are Curtailments a Balanced Water Use?

A Better Solution for Drought Resilience

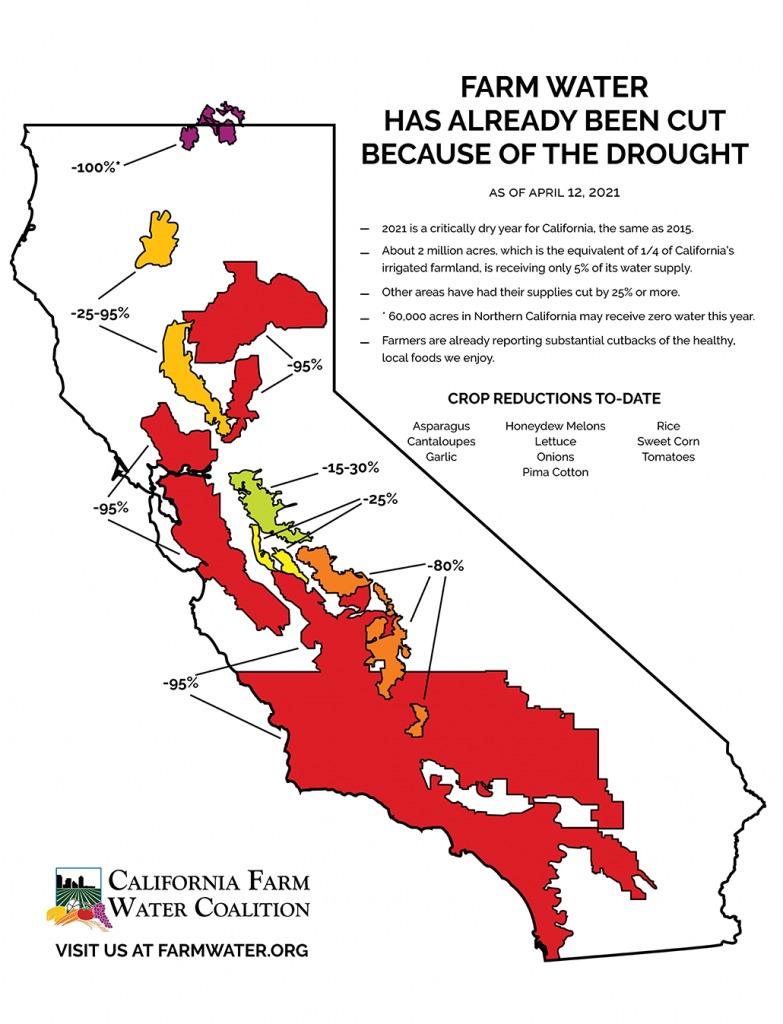

Map Shows 2021 Farm Water Supply Cuts

Click here to see the latest map. Updated: June 2021 California farms are bearing the brunt of this year’s short water supply and have been forced to reduce the acreage of popular California crops, such as asparagus, melons, lettuce, rice, tomatoes, sweet corn, and others. Water supply reductions mean fewer fresh fruits and vegetables for […]

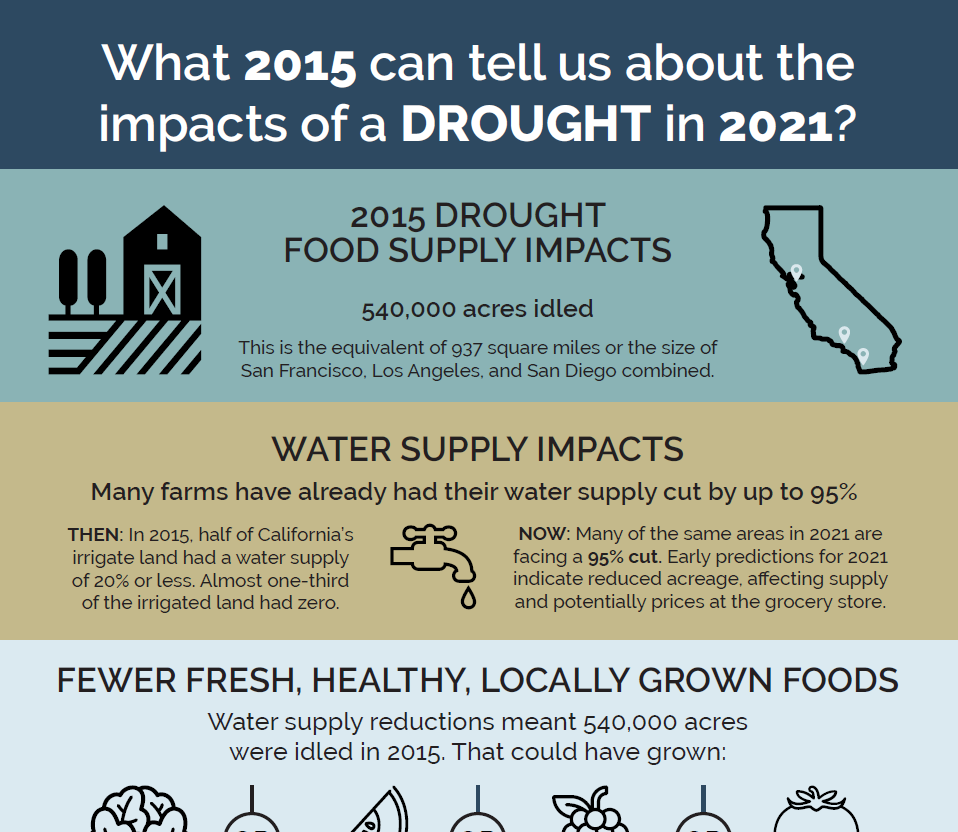

What can the 2015 drought tell us about the impacts of a drought in 2021?

Looking for a good primer on current water use issues?

This weekend, Bakersfield Californian columnist Lois Henry published an informative piece on the water management issues that nearly resulted in loss of water to millions of Californians. Henry’s column is well worth a read: in addition to providing a history of this year’s numerous Federal tinkering with water allocation, it also touches on what motivated […]

Many Delta Stressors Impacting Delta Smelt and Delta Health

There are far bigger issues affecting the Delta than water exports and returning to a time prior to Western development is unrealistic. To describe the Delta as altered is to say that New York City is populous or California water politics contentious. Since the 19th century when locals began to reclaim the marshlands, dike the […]

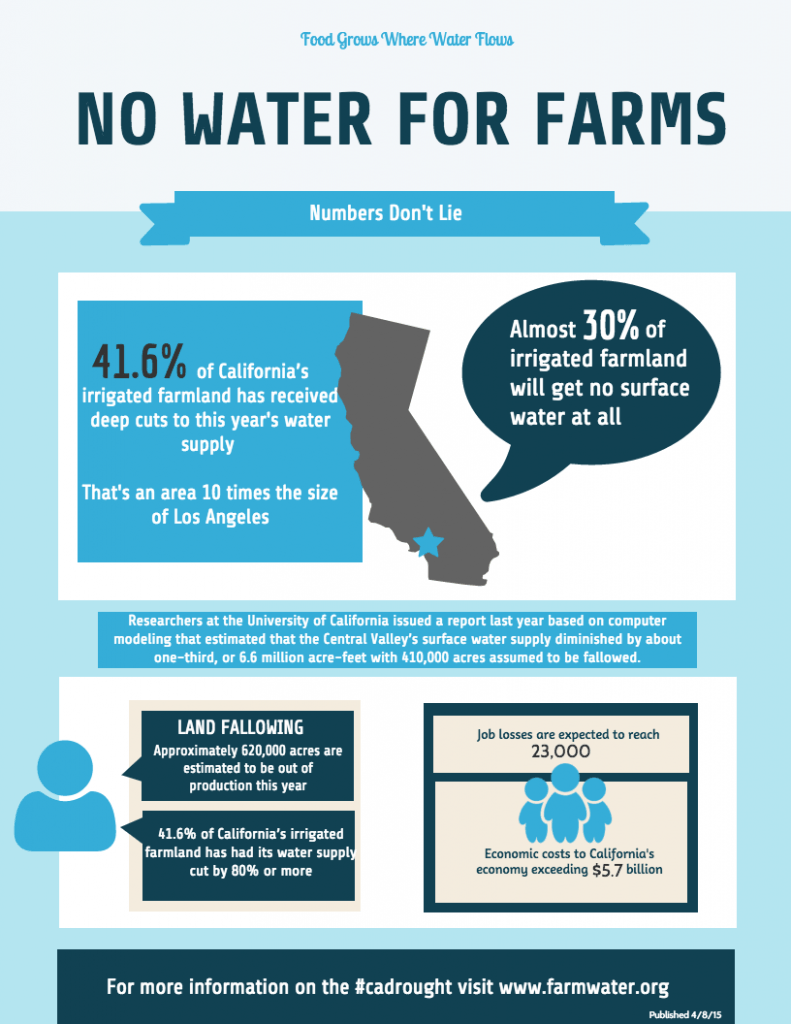

Over 41 percent of California’s irrigated farmland loses nearly entire surface water supply

Over 41 percent of California’s irrigated farmland will lose 80 percent or more of its normal surface water allocation this year, according to a new survey by the California Farm Water Coalition. The survey of agricultural water suppliers conducted the first week of April shows that 3.1 million acres, or 41.6 percent of California’s irrigated […]

Opposition to California Drought Legislation is Misleading

Opposition to H.R. 5781 is Misleading H.R. 5781, Congressman David Valadao’s drought relief bill requires water exports to stay within the existing salmon and Delta smelt biological opinions. Concerns raised by NRDC’s Doug Obegi are a red herring to thwart progress on providing water to a parched Central Valley. Exports may increase, as Obegi says, […]