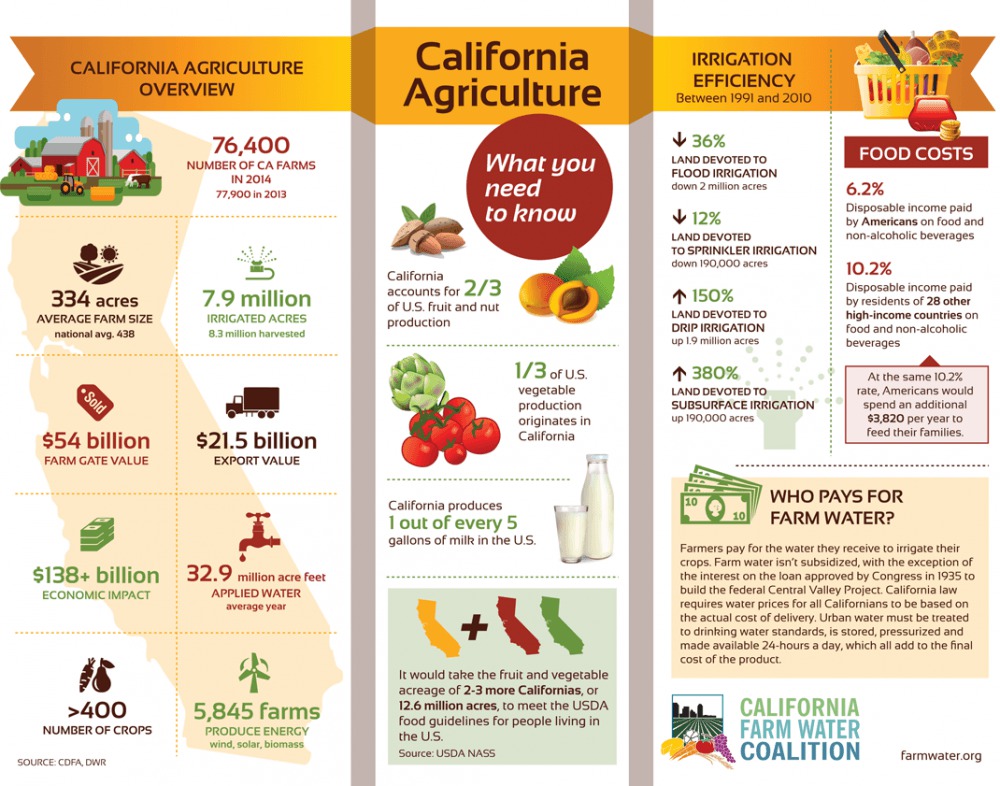

California’s farms are an important part of America’s food and fiber network. Our farms are among the most efficient in the world. Learn more about the important role California’s farms play in producing food and fiber for us all with this fact sheet.

The bleeding of agriculture

Approximate number of acre-feet of fresh water flushed to the ocean since December 1, 2015 One acre-foot is 325,851 gallons. It is enough water to meet the household needs of two California families for an entire year. Every day more than 6,600 acre-feet, or more than 2 billion gallons, of precious water is flushed to the ocean. […]

Timing is Everything

Timing is Everything. NRDC’s Doug Obegi wrote in a recent blog that we’ve captured and diverted too much water in the state’s reservoirs in January. He claims that “prevailing science” indicates that we shouldn’t be diverting more than 20 percent of unimpaired flows but he doesn’t tell us what science that is. A link in his blog […]

California groundwater pumping impacts preventable

CBS News recently focused on the impacts of groundwater pumping in California, but the causes were avoidable. Improving the reliability of surface water to avoid extracting groundwater from aquifers was a primary goal of California’s water projects. The reality is, California groundwater overdraft impacts were preventable. We applaud 60 Minutes for discussing the important issue […]

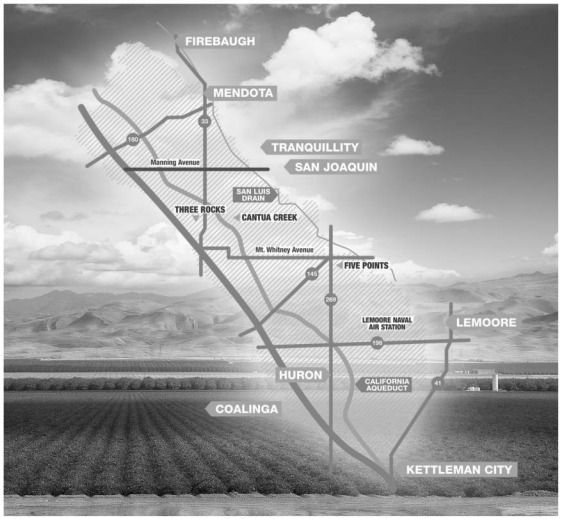

Westlands Water District: Straight Talk About Agriculture, Saving Water and Drainage

The Los Angeles Times recently published an intensely critical article about Westlands Water District, which recited many of the false, misleading, or outdated claims made by some of its critics over the years. The Times’ editors refused to print an Op-Ed that the District offered in response. As a result the District has taken out […]

Almonds

[audio src="/Content/FarmWaterMinute/almonds.mp3"]

Did you know that almonds have long been a treasured food? Eaten by pharoahs and traders of the silk road, almonds are even mentioned in the biblical accounts.

Spinach

[audio src="/Content/FarmWaterMinute/Spinach.mp3"]

Spinach is grown nearly all-year long in California. Most California farmers specialize in growing flat spinach! California farmers produce about 75% of the country’s total spinach crop.

Irrigation

[audio src="/Content/FarmWaterMinute/Irrigation.mp3"]

California has the second most irrigated acreage in the United States, with Nebraska alone irrigating more. California’s almost 8 million irrigated acres are dedicated to a wide diversity of more than 300 crops.

Discover California Ag in a ‘Farm Water Minute’

Have you been hearing more about California agriculture lately? Learn something new about California’s agriculture by exploring our fast and fun series of radio shorts – Farm Water Minutes!

Continue readingProcessing Tomatoes

[audio src="/Content/FarmWaterMinute/ProcessingTomatoes.mp3"]

California leads the nation in tomato production, producing approximately 95% of the nation’s tomatoes.